Below is a complete revised text of a post of 10 April 2024.

This post has been translated from Dutch into English with DeepL. It will be manually edited and streamlined soon.

Without much effort, we can recognise ourselves in an animal. Just like us: two eyes and two ears, and a mouth that wants to bite and chew. Arms and legs, legs, wings, fins: an ongoing evolutionary family relationship. And then, that remarkable common animal restlessness. We, animals, always look for it in movement. When danger approaches, we run away. When we smell a tasty snack or a fragrant peer, we sneak closer. The solution to both getting what is missed and avoiding what is irritating, uncomfortable and threatening is in our movements through space. If you don't find what you are looking for here, you move there. And if you find something there you don't like, you move elsewhere again. This relentless restlessness marks the kinship between us humans and other animals.

How different plants are. Entrenched in the place where they once sprouted as seeds, they cannot avoid or obtain by moving. They will have to find a solution for every challenge they face - on the spot. An unthinkable task for any member of the restless animal family. Biologist Stefano Mancuso, author of 'The Revolutionary Genius of Plants' notes:

Whereas animals react to changes in their surroundings by moving to avoid those changes, plants respond to the constantly changing environment by adapting to meet it.

And renowned French botanical illustrator Francis Hallé says in an interview: ....

When I entered the Sorbonne in Paris, I was not really interested in plants, but rather animals, indeed like 99 percent of students, by the way. Today. I like animals, but I can't take them seriously because they move all the time. …. For me, trees are much more beautiful than animals. Animals are dirty, noisy, and when they die, they smell awful. When a tree dies, it doesn't smell bad because its molecules contain less sulfur. I wonder if our initial relationship to trees is aesthetic rather the scientific. When we come across a beautiful tree, it is an extraordinary thing. ….

TOTEM

Humans mirroring themselves in animals are soon tempted into anthropomorphism. A small cuddly dog, yet direct descendant of the dreaded wolf, is given a fashionable jacket. And in the raised beak corner of a grinning Donald Duck, the illustrator draws white teeth. Alternatively, the mirror game leads to zoomorphism, in which humans, out of jealousy, would all too happily appropriate characteristics of the animal. That possesses primal physical powers, flashy speed and fearsome teeth and jaws, without which civilised man is no more than a sucker.

The animal as icon, as totem. The Hague, my hometown, has the stork as a city totem. The Scheveningen neighbours carry two herrings in their coat of arms. The orange footballers mirror the lion. Runners take an antelope as their totem, swimmers a sea lion, thieves a magpie, and weightlifters an Asian working elephant.

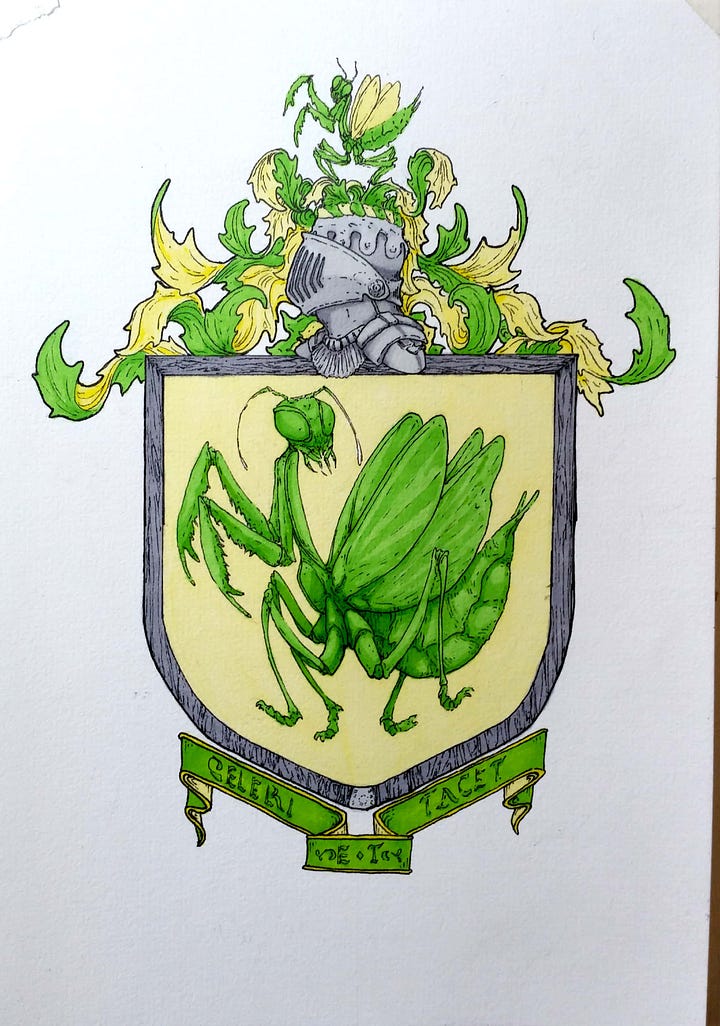

In the martial arts, it is common to look for art in the animal kingdom. Martial animal totems therefore come in many guises. The grenadier's bear hat, a dragon on a knight's shield, Bruce Lee's praying mantis and General Yu Fei's Eagle Claw.

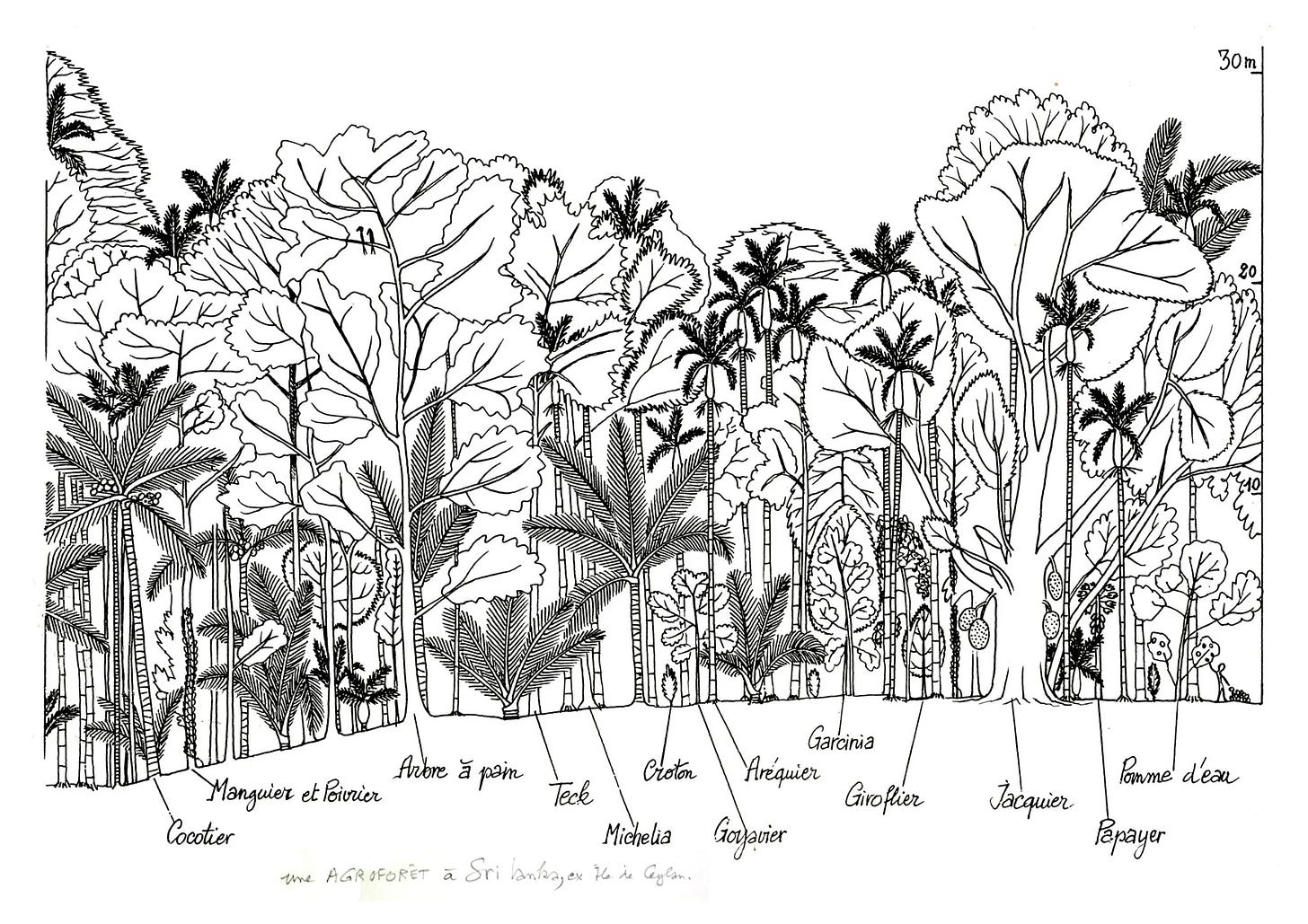

Tiger, crane, leopard, snake and dragon in the southern martial styles. The twelve Hsing I Chuan animals. The 'bear step' and the 'snake step' in I Chuan. But aren't we missing something? For the martial artist, animals certainly possess enviable properties. Traits you can imagine, imitate and perhaps one day call your own. But aren't there plants that can serve us as teachers and inspirations? Where are the plant and tree totems?

GREEN INGENIOUS

Plants are tied to the location of their original germination. Unable to dodge, run and flee, there is nothing left for them but to solve difficulties that arise on the spot. Plants developed an infinite range of self-defence mechanisms. Often without much on the outside, they creatively face off against aggressive munchers and grazers: bark, spines, thorns, scent, poison and intoxication. Our science has only explored and mapped a fraction of plant warfare and seduction techniques. Who said plants just stand there defenceless and ignorant of martial arts?

One wonders why plants hardly feature in martial heraldry.

Perhaps an idea to adopt the nettle as a martial totem?

SF weaponry?

Selective defence ...

Chemical weapons ...

Deadly to micro-organisms, therefore also a vital drug ...

Stand in a natural environment. In a forest or park, your backyard. Don't close your eyes completely, but give them rest, stand with eyes half closed Instead of standing, you can of course sit. Focus your attention on what smell enters your nose. At first, you may smell little, perhaps just your own skin or soap or sweat, or your clothes. But soon you will become aware of smells you did not notice before. Pick up the scents that air currents or wind carry with them, faint or strong.

When you look at an object, you perceive reflective light: a visual touch with the light waves as messengers. But the smell you breathe in through your nose is an essential part of that other. A fleeting part that separated itself from the whole. In French, the word 'essence' is used; the scent as the essence. Take ten minutes to identify with the world of smell. Breathe in your environment.

What can bring us close to chemical world of plants is navigating and orienting through the nose. Like plants, we live in a world of smell, although for most of us this is an understated - and discounted - reality. Scents are immediate, instinctive, unrelenting, and trigger memories. Much of the sea of scent we live in is of plant origin. A dizzying pallet. When a plant cannot travel any distance because of its roots, there is always the wind. It carries the plant's scents away over distances and brings the scents of others to it. The lack of a nose in no way prevents the plant from perceiving scents.

REGENERATION AND RESILIENCE

Parallel to the development of martial skills, the practitioner explores the paths of health and the art of living long. And to whom would you best turn for inspiration? The vast majority of animals are already elderly or deceased when a healthy oak or beech tree is only in its adolescence. The age of most animals is dwarfed by the age of many plants.

It is a true miracle that a starfish can grow a new arm after losing one. Doesn't that seem convenient to you? But a random tree loses branches throughout its life, and after a short time, they are all replaced by new ones again. Whereas an animal has life functions concentrated in specific organs, the plant is modularly built. All parts are replaceable and renewable. Even if the storm or a fire has destroyed the above-ground tree, the invisible root part is often still alive and kicking. And lo and behold, only so soon after the devastating fire, new greenery already reappears.

In US Utah, Pando grows. Pando is not a single tree, but a forest of more than 40 hectares of ratchet poplar. All 40,000 trunks share the same root system, and while the single trunk is born and dies, Pando as a whole is ancient, 14,000 years. Isn't that a fascinating example of regenerative power?

The practice is uncluttered. Find a suitable environment: a quiet corner in a city park, a balcony overlooking a tree, the dunes, your living room with plants in the window sill, a forest. Stand upright, with your arms along your body (wu chi zhuang). Your hands on your back, your hands at your sides, or both palms on your belly are other good options. Relax your knees, relax your gaze. Look at the greenery freely.

In our usual dealings with our bodies, our senses - especially our eyes - get a lot of attention. The hands, and our thinking, also get a disproportionate share of it. Consciousness is dragged to where there is a lot of activity. And where strong sensations occur, sensations of heat or cold, pressure, itching and pain. Consequently, some parts of the body receive little or no attention, others an excess.

Take the tree or plant in your immediate environment as an example. The plant has a modular structure, it is proportionally developed. All branches and leaves share evenly in burdens and pleasures. Even underground, where we cannot directly perceive the plant, the relationship between its various parts is egalitarian. All the root tips penetrate the earth simultaneously and evenly. Of course, there are obstacles to perfect radial development above and below ground: shade, a lack or excess of water, a rock, a severed branch, a column of gnawing caterpillars. That very fact shows that the vital power of trees and plants lies hidden in the collectivity of the parts.

The practice of standing chi kung attempts to awaken a similar latent collectivity within the practitioner's body. It is innate to us, but there are many reasons and circumstances for a profound disruption of the inherent power of oneness. The zhan zhuang practice opens access to previously neglected and forgotten body zones, the personal terra incognitas. Step by step, the whole body is brought back within the context of consciousness and breathing. The I Chuan tradition speaks of awakening 'huan yuan li', of the power of collectivity, of collective resilience.

lees verder: